From The Editor's Desk

This month, China announced severe restrictions on rare earth exports to the United States, prompting President Trump to threaten 100% tariffs on all Chinese exports and to strike a critical minerals deal with Australia. By applying its own version of a Foreign Direct Product Rule, Beijing now requires licenses from its Ministry of Commerce to export products containing even a trace of Chinese rare earth content or made with Chinese technology. This maneuver effectively gives Beijing veto power over critical inputs used for everything from fighter jets to semiconductors.

The United States has deeply integrated its supply chains with China over decades, making this a significant near-term challenge. But it may also be the forcing function needed to build a more resilient American supply chain in the long term.

What Are Rare Earths?

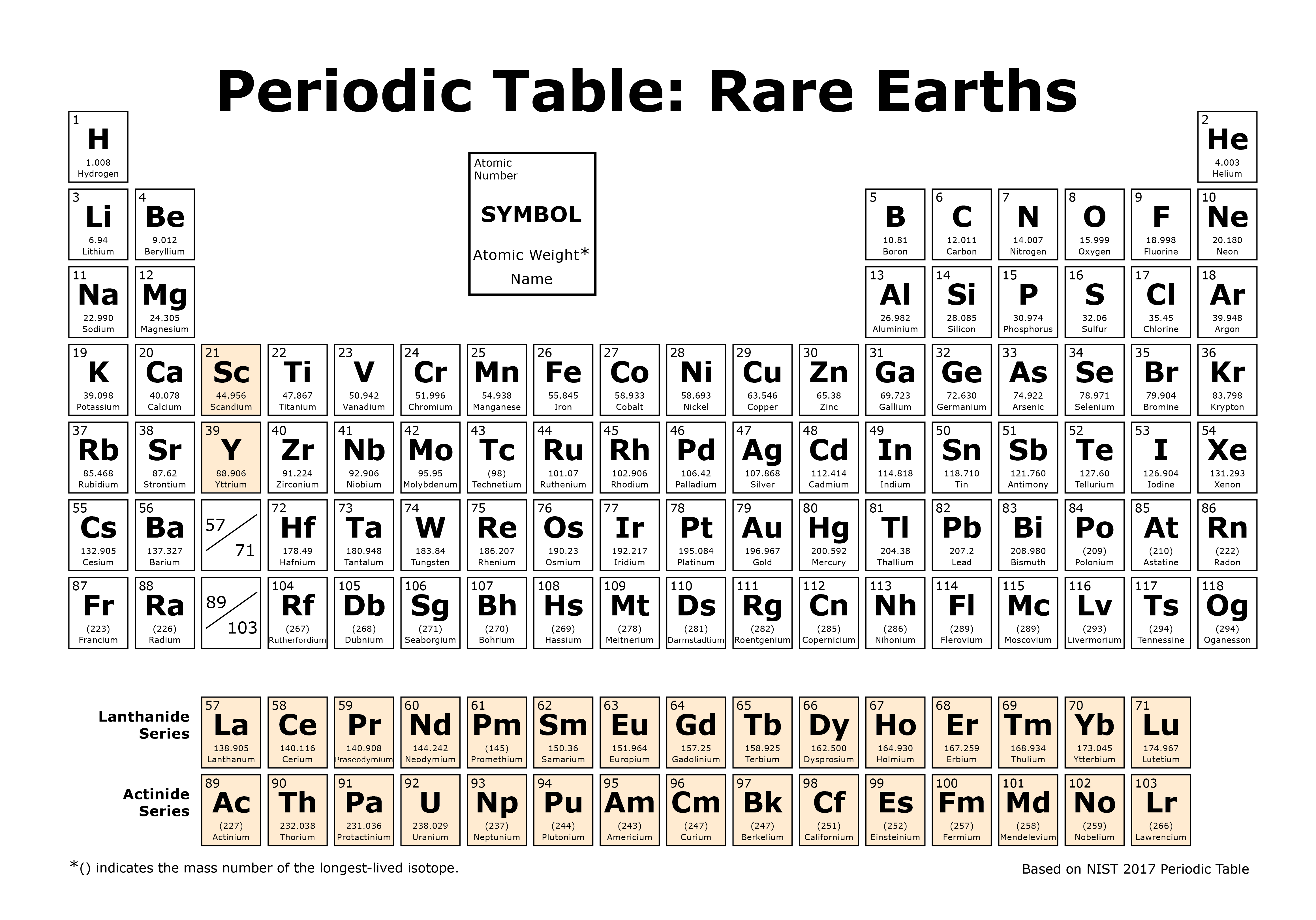

Rare earth elements (REEs) are a group of 17 metals with unique magnetic and luminescent properties. Their name is misleading; they aren't rare, but it's uncommon to find them in concentrations high enough for profitable mining. They are divided into two classes:

- Light rare earths (LREEs) are more common and form the foundation of powerful magnets. Neodymium, for example, is used to create magnets found in wind turbines and EV motors.

- Heavy rare earths (HREEs) are much scarcer. A neodymium magnet alone can't handle the heat of a powerful motor, but adding a small amount of the HREE dysprosium gives it the necessary heat resistance for demanding applications like a weapons system.

The real difficulty is in the processing. Separating these elements from each other is challenging because they have nearly identical chemical properties. Retrieving them requires a costly and environmentally hazardous series of steps, making it unattractive to countries like the United States with strong environmental protections. China has been more than happy to pick up the slack.

China’s Restrictions, Explained

China’s new policy, taking full effect December 1, creates three layers of control:

- Direct material controls: These controls restrict the export of raw materials, expanding restrictions from a previous list of 7 REEs to include five additional heavy rare earths used in applications like laser targeting, fiber optics, and quantum computing.

- Indirect product controls: China’s new Foreign Direct Product rule extends China's authority globally. Any product with over 0.1% Chinese-origin rare earths—from a microchip made in South Korea to a sensor made in Germany—would now require an export license from Beijing.

- Intellectual property controls: The new rules restrict the export of Chinese technology for rare earth refining and magnet-making. Chinese citizens are now prohibited from supporting overseas rare earth projects without state authorization.

These measures were timed for maximum leverage, announced just weeks before a planned Trump-Xi summit, and giving Beijing nearly two and a half months before their declared deadline to use the threat of implementation to extract concessions on issues like tariffs and America’s own export restrictions on Chinese technology.

China’s Advantage

China dominates the entire supply chain, accounting for 70% of global rare earth mining, 90% of processing, and 93% of the world's high-strength rare earth magnets.

MP Materials, operator of America's sole rare earth mine, illustrates the scale of the challenge. The company's California mine is rich in light rare earths, which it separates and ships to its Texas facility to produce finished magnets. But even with a new DoD-backed expansion planned for 2028, MP Materials would produce roughly 8% of the 138,000 tons China output in 2018, and because these efforts are mainly focused on light rare earths, it doesn’t resolve America’s critical need for a heavy rare earth supply.

The American Response

The U.S. government is intervening directly. As we wrote about in September's newsletter, the Department of Defense invested $400 million in MP Materials and committed to a 10-year offtake agreement for 100% of the facility's output. Critically, the agreement includes a price floor more than double current market prices (which are artificially depressed by China’s own state support for its rare earths industry). This isn't a market-driven investment; the government is paying a "sovereignty premium" to ensure domestic capacity exists at all.

Looking Ahead

Federal and state support for domestic production of raw rare earths, rare-earth magnets, and substitutes is driving innovation along three dimensions:

- Tech-enabled exploration, mining, and processing: The high-tech mineral prospecting sector has become a key target for venture capital, with AI-driven startups like KoBold Metals raising nearly $1 billion. Concurrently, the Trump administration is using industrial policy to de-risk the market. This includes direct funding, such as grants to mineral processing startup Alta from DARPA and the State of Colorado, and investment from In-Q-Tel. It also includes critical policy accommodations; following a recent executive order, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) initiated a seabed mineral leasing process, a move that would enable deep-sea mining companies like Impossible Metals and The Metals Company to freely operate.

- Materials science and rare earths substitution: In the race to develop rare-earth-free permanent magnets, iron nitride technology is the current frontrunner, in part because strategic government funding is accelerating its path to market. Niron Magnetics is a leader in the commercialization effort, leveraging a $17.5 million grant from the DOE's ARPA-E program and another $10 million from the state of Minnesota to directly support the build-out of its manufacturing capabilities.

- Reclamation: Government is also partnering with start-ups trying to recycle rare earths, like Phoenix Tailings, which recovers rare earths from mine tailings and has received over $4.1 million in federal and state grants, as well as startups recycling discarded electronics and batteries. Companies in the latter space like Redwood Materials and Ascend Elements are building industrial-scale facilities. These efforts coincide with a range of broader incentives like a $500 million DOE program for battery recycling.

These are significant commercial opportunities, but they come with a giant asterisk attached. Today's export restrictions may not last. If the market is reopened to low-cost Chinese supply, the demand for more expensive, domestic alternatives could evaporate, leaving only aggressive federal intervention to sustain America's nascent industry.